Crafter and activist Betsy Greer credits a Halloween parade in New York City’s Greenwich Village almost a decade ago with giving her the idea to leverage handmade things for political commentary. As she watched the witches and zombies and ghosts pass by, giant papier-mâché puppets of George Bush and Al Gore, who were vying for the presidency that year, appeared in the distance. As the puppets floated down the street, held up by the people who made them, the crowd became quiet. That reaction stunned Greer. She continued to ponder the response while she knitted on her couch later that night and thought about the puppets’ ability to convey political messages without any speeches or signs involved.

That realization stayed with Greer for a few years as she joined and started her own knitting circles. She also recalled how her grandmother, who taught her the basics of knitting, would volunteer her time to knit hats for newborns in a local hospital. She put the two together and saw how she could use crafting to engage in issues and movements that were important to her. “Some people want to make a change in standing up and yelling, some people make a change in writing checks, and some people make things,” Greer says.

So she grabbed her needles and yarn and started knitting items to donate to people in need, such as vets for Afghan children and scarves for survivors of domestic violence. Today, Greer is known as the godmother of “craftivism,” a term that represents the intersections of crafts that Greer coined in 2003 after a friend in her knitting circle suggested it. Craftivism comes in numerous forms such as needlework, woodwork, and fiber arts.

Back then, the term only brought up two hits on Google’s search engine, Greer says. But now, one could expect over 200,000 results and see how craftivism has been tied to numerous movements including feminism, environmentalism, and anti-capitalism, and political events such as President Donald Trump’s inauguration on January 2017. And with the knitting website Ravelry’s ban on all pro-Trump content on its platform in June 2019, people continue to reflect on craftivism’s role in political dissent and community building.

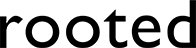

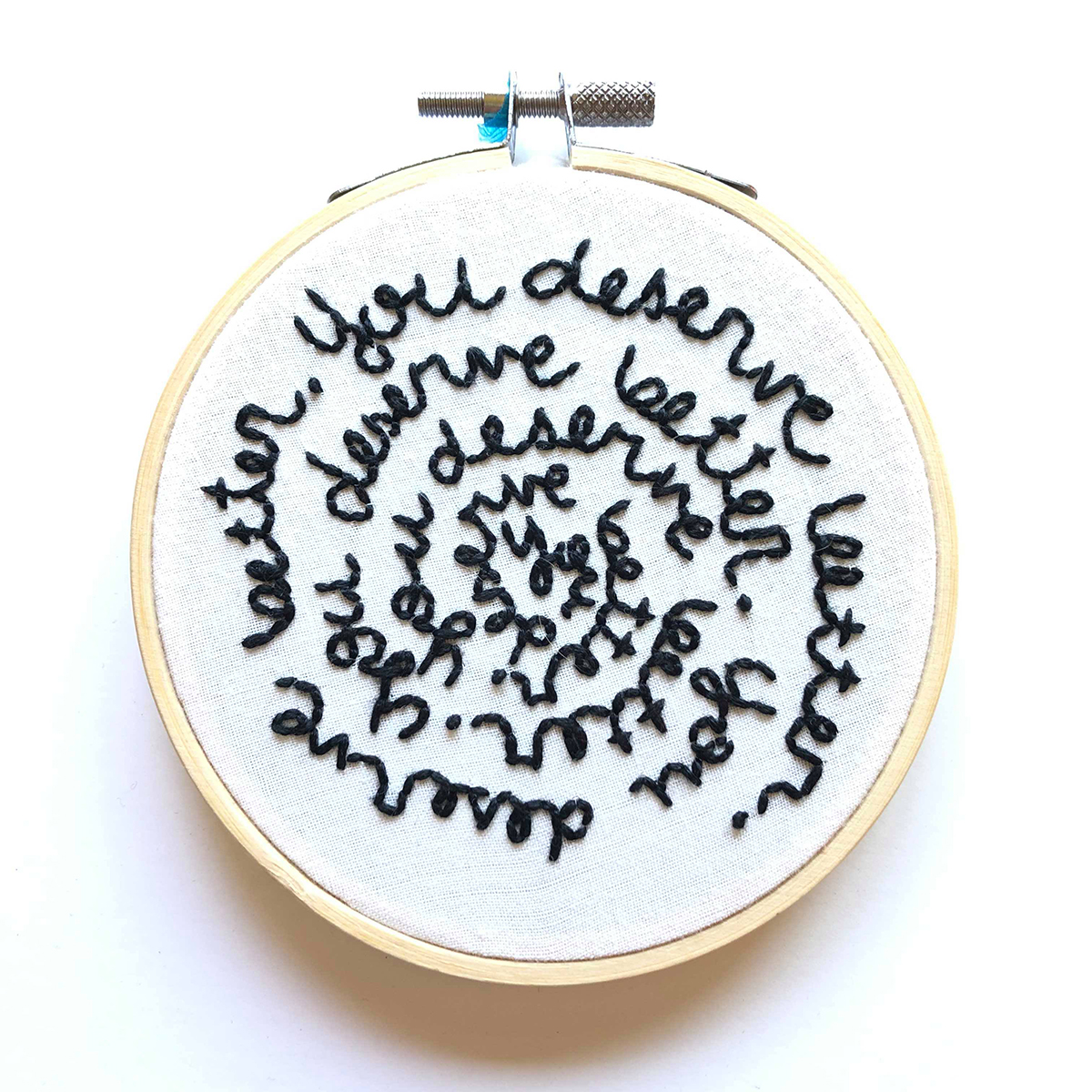

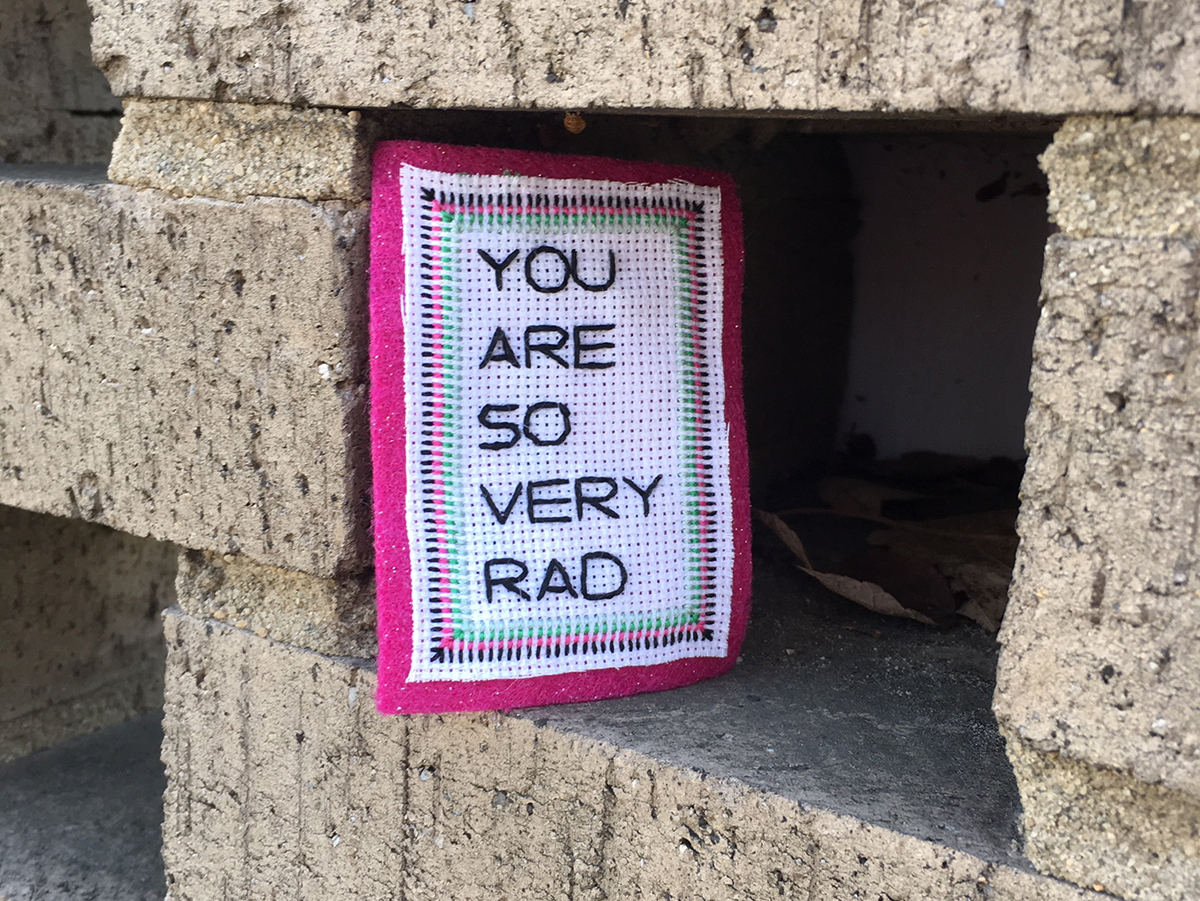

Closeups of hoop craft projects. Top hoops are made by Southern artist Heather Andresen. The one on the top left was inspired by anti-capitalist ideas, and the one on the right is in support of abortion clinics. The bottom left hoop is made by Stephanie Rohr, and the bottom right is made by Sarah Corbett.

Part of the reason why craftivism remains relevant is because exchanging ideas is inherent in the craft community, whether through sharing knitting patterns or teaching each other new skills, explains Tal Fitzpatrick, a Melbourne-based artist and researcher. Fitzpatrick, who completed her doctoral dissertation at the University of Melbourne on how people use craftivism to engage in democracy, says this community has grown with makers and artists increasingly sharing their work on social media platforms such as Instagram and Facebook and getting others to participate in projects through hashtags like #100actsofsewing where people make 100 dresses in one year while exploring body-positivity and hyperconsumerism. And Fitzgerald believes the movement will keep expanding. “It’s going to continue to have quite a lot of relevance and importance considering the political situations around the globe and the existential kind of issues like humanity having to deal with climate change,” Fitzpatrick says.

In that way, it kind of acts like a Trojan horse … so where in some spaces, activists aren’t welcome or their behavior is frowned upon, you can sneak in crafts.

Yet crafting for activist reasons isn’t a new phenomenon; in fact, there’s a rich history behind it globally, particularly when it comes to textiles and fiber work. Historically, crafting has been a space relegated to women and viewed merely as domestic work such as knitting clothes or socks, says Juilee Decker, an associate professor of museum studies at the Rochester Institute of Technology’s performing arts and visual culture department and co-curator of the “Crafting Democracy: Fiber Arts and Activism” exhibit that launched in August 2019 in Rochester, N.Y. But women also used crafts such as knitting, sewing, and embroidery to participate in public discourse right from their domestic spheres — from how the Daughters of Liberty spun their own yarn and wool into fabric to boycott British goods during the American Revolution to women in the U.K. using their needlework skills to make banners and badges to support the suffrage movement in the early 20th century. Craftivism also was used by other minority groups such as the LGBTQ+ community when gay rights activist Cleve Jones introduced the Aids Memorial Quilt in 1987 to commemorate those who lost their lives during the AIDS epidemic and Black communities such as those in Alabama’s Gee’s Bend who have turned to quilting to tell their stories across generations.

As a medium, crafts are used for activism because they’re accessible and bring a sense of familiarity to people, which makes their messages easier to understand compared to other artforms, Decker explains. “They may not understand the processes, techniques, or methods in some cases, but the familiarity makes it inviting,” she says. “Oftentimes, people don’t know differentiations between types of paints for a painting or types of stone when looking at a stone sculpture, but with a familiar material, you sort of bridge that gap.”

Furthermore, crafting is non-confrontational because people don’t traditionally understand it as a form of activism compared to marching or donating for a cause, Fitzpatrick explains. “It’s able in that way to start complex conversations without necessarily pulling straight away into that us versus them kind of othering,” Fitzpatrick says. “In that way, it kind of acts like a Trojan horse … so where in some spaces, activists aren’t welcome or their behavior is frowned upon, you can sneak in crafts.”

One example is Chicago-based cross-stitch artist Stephanie Rohr’s work. Rohr, who published a book called Feminist Cross-Stitch in 2017, went from stitching a collection of humorous memes and pop-culture references to politically-driven statements like “Nasty Woman.” “Maybe from [people] enjoying that funny cross-stitch, it’ll actually make them think about the issues behind it in a different way,” she says.

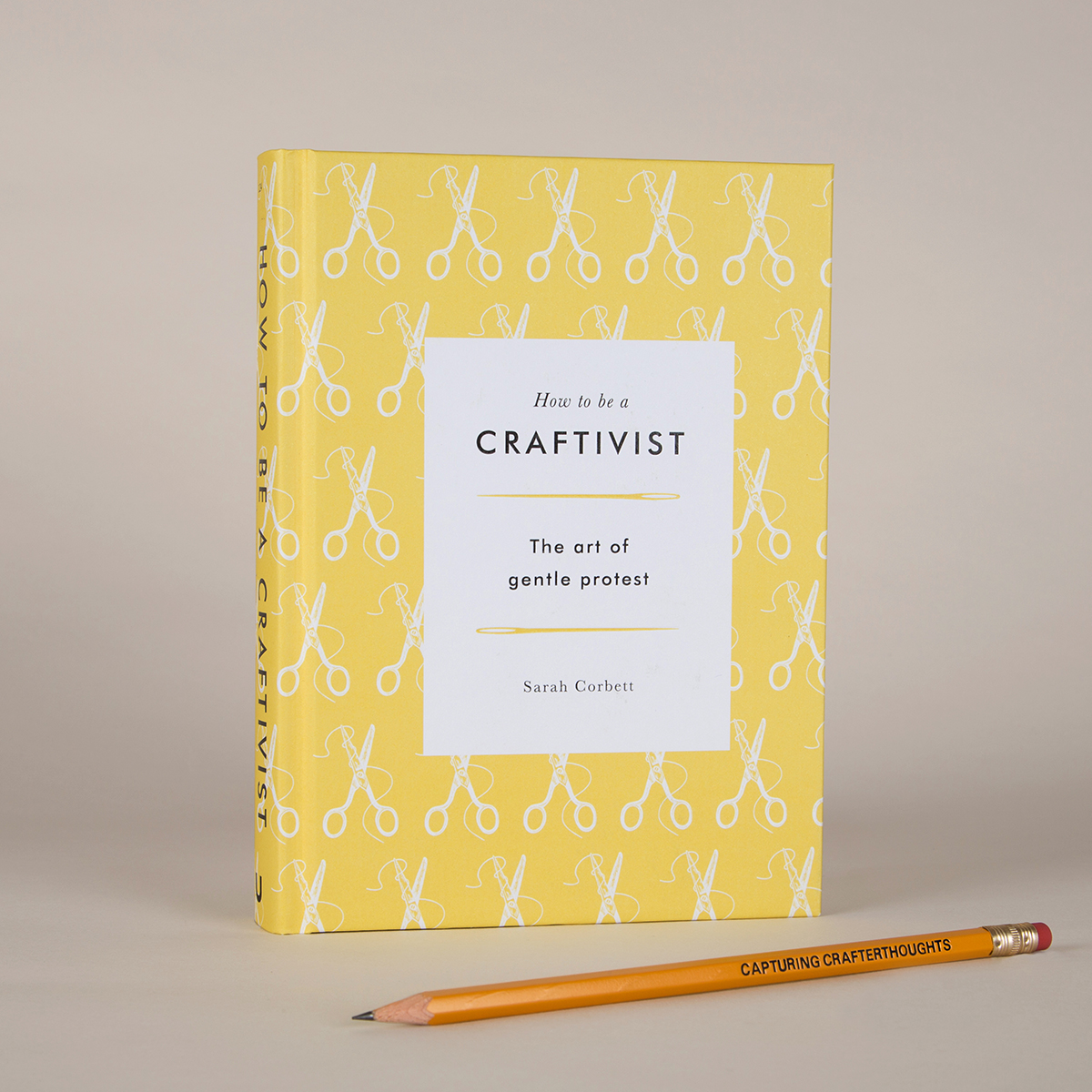

Craftivism also creates a space for people who may not immediately see themselves as activists. For instance, Sarah Corbett, the founder of Craftivist Collective, a London-based organization that connects craftivists worldwide, refers to the term as a gentle protest that provides an avenue for introverts or people who want to participate in a certain movement without having to use a megaphone or fearing for their well-being. “Crafting puts you in the position to calm down and do some critical thinking in activism,” Corbett says.

Also, even though some people may view crafting as traditionally done by women, men are participating in craftivism, Greer says. Greer, who also wrote the anthology Craftivism: The Art of Craft and Activism in 2014, says that she’s noticed more men show up to her book events and attend her cross-stitch classes over the years. “There are always more men than I would think there would be, which is great because that means men are self-identifying as feminists, and they’re also getting into the craft which has been seen as a womanly thing,” Greer says.

For example, cross stitcher and patch-maker Stephen Broder of Sacramento, Calif. says craftivism allows him to examine his masculinity and male privilege. “What I like about crafting is you can be really direct and sort your thoughts out a little better,” Broder says. “You can get your points across better than you would otherwise.” He says he’s always wanted to design and wear clothing with feminist statements, but he wanted to make sure it was alright for him to enter the craftivist space as a white, cisgender male. Today, he says one of his favorite designs is the phrase “boys will be boys” with the second “boys” crossed out and replaced with “held accountable for their actions,” embellished on a pair of jeans.

I think we silence ourselves a lot in different ways in society because we feel like we’re not enough. By doing something like crafts and putting feelings or emotions on it, it can be a way of starting to speak up.

However, there are still minority voices that lack visibility in the craftivism movement — particularly Black people despite their long history of crafting, according to Jeannette Sloan, founder of the online accessory shop SLOANmade. Sloan, who’s been designing knitting patterns for over 20 years and written several books on hand-knitted accessories, curated a list of designers and crafters of color in 2018 to bring attention to their work and issues regarding race, diversity, and inclusion. She also wrote an article called “Black People Do Knit” for Knitting Magazine where she talks about how there’s very little written about the history of Black knitters and how they’re rarely shown in books and magazines as makers. “We do craft, we do design, we do tech edit, and we’re good at it,” Sloan says.

Through her research, Decker has also seen a trend of makers using crafts to speak out about the country’s racist history. She explains that there are people who use yarn or other types of fiber to cover up monuments and memorials that relate to the Civil War, which is often called “yarn bombing.” One example is The Kudzu Project, started by a group of knitters from Charlottesville, Va. who started covering Confederate statues with knitted kudzu in response to the Ku Klux Klan, neo-Nazis, and other white supremacist groups protesting their removal from public parks in 2017. Decker says they picked kudzu, a non-native invasive plant, for the message it carries with its nickname — “the vine that ate the South.” “Since [the monuments] are out in the public space, it’s sort of reclaiming that space by covering it and pushing back on the fact that it’s a visual representation of prejudice,” Decker says. She also says she’s seeing communities gathering together to craft for the purpose of craftivism. People can connect not through similar hobbies, like crafting, but through their shared beliefs and values. “They come together as a community like you would have a knitting circle in the 19th and early 20th century,” Decker says.

Back in Durham, N.C., Greer continues to share activist messages through her embroidery and knitting. She also started a project two years ago called “You Are So Very Beautiful” that involves making handmade signs of daily affirmations with anything from needlework and painted rocks to carved wood and cakes, then placing that sign where someone can see it. Greer also continues to inspire other makers and artists to craft for themselves and share their own beliefs or help give others a voice in public discourse. “I think we silence ourselves a lot in different ways in society because we feel like we’re not enough,” Greer says. “By doing something like crafts and putting feelings or emotions on it, it can be a way of starting to speak up.”