Marrisa Poe is a contributing writer and business officer for…

It took a move to the desert for Juliana Ciano, a homesteader from New Mexico, to appreciate the severity of the water crisis. “I grew up in Minnesota, where people are less mindful of their water use because they are surrounded by water,” says Ciano, 34, who grew up with an appreciation and concern for the earth — camping, working on a ranch, studying sustainable systems. Ciano and her family live on two acres and grow a variety of fruit trees, vegetables, and herbs. “When I moved to the desert, the mentality here is very, very different. Water is so precious. We are really counting every drop and trying to be as aware as we can of what we’re using,” she says. Part of that awareness involves finding ways to reuse water. “We reuse all of our water from washing the vegetables to watering the plants and we catch rainwater,” says Ciano.

Several recent laws, initiatives, and government studies reflect Ciano’s concern for the need to conserve water and highlight the need to find ways to reuse it. According to the 2014 Government Accountability Report, 40 out of the 50 states will experience water scarcity in the next 10 years. Ciano’s New Mexico, along with Arizona, Nevada, Colorado, Wyoming, California, Utah, and Mexico (where the Colorado River serves as a key water source for people in the area), is making plans to enforce water conservation with the signing of the Drought Contingency Plan this past May.

Amy Haas, the executive director and secretary of the Upper Colorado River Commission, which focuses on the Upper Basin Division states (New Mexico, Utah, Colorado, and Wyoming), is part of a team trying to change water habits in the area. “I think that this is something that is necessary and that will help the states become more resilient. We are in our 19th year of the drought of record on the Colorado River,” Haas says. “We have seen the effects of climate change basically exacerbate that drought of record.”

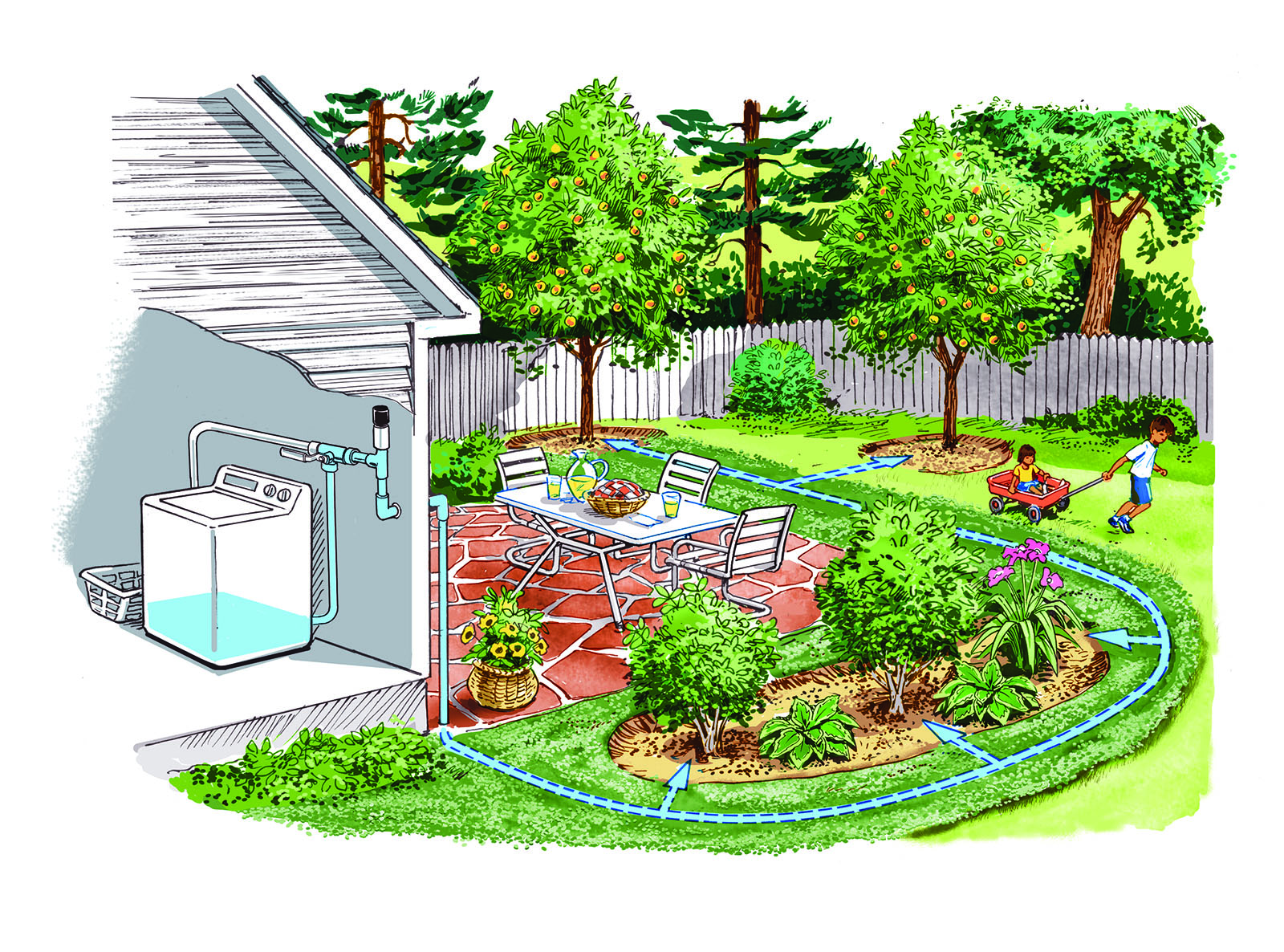

Changing water habits is a challenge. The average American uses 88 gallons of water a day. “We have a major mentality in our culture that when we are done with something, it just goes away,” says Ciano. But Ciano and a growing number of water advocates and consumers are turning their attention to systems that aid in the intentional use of water, and systems play a key role in water conservation: Installing an efficient fixture or appliance can reduce water consumption by 20%. And one appliance used to combat water use that is gaining more attention is grey-water systems, which recycle water from showers, tubs, washing machines, and sinks by separating that water from the water used in toilets. “Grey-water systems could save anywhere between 120 to 190 gallons of water per day with an average savings of 50,000 gallons of water per year in an average household,” says Gus Meza, a senior water efficiency specialist for the West Basin Municipal Water District.

For grey-water systems, prices can vary depending on the size of a resident’s system and what sort of grey water coverage they want. There are various systems, from Do-It-Yourself to using a company that specializes in and will install them. Do-It-Yourself systems can cost as little as $150 to $300 while some of the most complicated grey-water company installations, like a sand filter to drip irrigation, can cost as much as $10,000. Yet many people still don’t know much about grey-water systems. “The biggest hurdle for grey-water systems for receiving wider exposure is regulation,” says Remy Sabiani the owner of Water Wise Group, a company that sells grey-water systems all across the country. Sabiani moved to the United States 10 years ago and saw the need for grey-water systems as an alternate way to conserve water, especially as people became more involved in water conservation.

Most irrigation systems combine the water from showers and washing machines with the water from the toilet (referred to as “black water”), making it unusable. In fact, grey water accounts for up to 75% of the wastewater in households and about 69% of domestic water consumption. For now, only 7% of United States households are reusing grey water, and the majority of those households reside in prime drought territory, the southwest region of the country. But that water from everyday tasks such as washing hands and clothes could easily be used for activities like watering flowers and grass.

The use of grey-water systems started back in the 1990s when the L.A. Department of Water and Power and Department of Public Works installed grey-water systems in eight homes for drought research. Although they found that the installations reduced water consumption by an average of nearly 50% per household, California legislators passed strict regulations on grey water use in 1992 because they were afraid that the systems would cause major ground-water pollution. While the legislation made it difficult for homeowners to install their own grey-water systems, they still slowly gained popularity in Western states as drought issues expanded to communities there.

But as usage and laws governing that usage spread, a crazy quilt of differing regulations on different systems for different states emerged. Grey water use is only allowed in 20 states because most states view grey water as a questionable water source, one that is not completely void of contaminants. “Some of the most simple grey-water systems that work really well don’t require a permit in many of the western states,” says Laura Allen, a founding member of Greywater Action, an educational group based in Berkley, Calif. that teaches people how to conserve and reuse water. “Legalities around grey water are just completely different state by state.” Today, states with high drought probability such as California, New Mexico, and Arizona embrace the water conservation technique, especially with increased pressure from grey-water advocates.

We need to be treating water as a precious resource. So it does not make any sense to waste it.

In California, for example, the “laundry to landscape system” is one of the more popular options. Typically, a washing machine features a pump that directs the water into the sewer or septic system. But this system features a diverter valve to redirect the flow. The valve enables one to turn their grey water to the sewer or the landscape, which makes it really convenient, Allen says. Then, the owner decides how much water goes to their holding tank for their plants or grass and how much goes into the septic system.

Regulations are not the only issue facing grey-water systems. They also struggle with a publicity problem. Many consumers see them as difficult to install, a challenge to maintain, and simply intimidating to contemplate. But Amanda Bramble, a permaculture and grey-water enthusiast for 25 years — so much so Ciano calls her the “queen of grey water” — could serve as a poster child for the ease and sustainability of the systems. “Grey water is important not just for homesteaders, but for everyone,” Bramble says. “It’s ridiculous to not be using our water as many times as we can.” Bramble owns three grey-water systems to accommodate her sustainable lifestyle on her homestead. Her systems provide water for her greenhouse, a permaculture guild which is similar to a small forest, and an asparagus bed. “I would say there is a great chance that it will go well for anyone,” Bramble says. “You just need to some basic plumbing know-how.” Her systems are made up of simple CVC pipes and old planting pots that help separate her grey water so that it can filter into the correct sections of her homestead.

Beyond serving as a grey-water role model, Bramble also works to educate people about the systems, a critical piece in making the use of grey-water systems more popular. Bramble is the director of the Ampersand Sustainable Learning Center, a place in Cerrillos, N.M. that offers the opportunity to learn and cultivate sustainable skills to anyone interested. People can either come to the property, which she runs with her husband, or book a visit. “It was just the way that I felt that I wanted to live and wanted to influence the world,” says Bramble. “We need to be treating water as a precious resource. So it does not make any sense to waste it.”

And while some states are becoming more aware of the need for water conservation and implementing laws to promote water consciousness, it has not become a nationwide priority on the same scale as the desert states. “We are totally disconnected from the whole cycle of water, where it comes from and where it goes. What happens if we use too much?” says Allen. “We just don’t see the effects of our use of water and what we put into the water.”

Grey water is important not just for homesteaders, but for everyone.

Allen also sees education as an important tool, and it’s a key mission of her organization, which seeks to raise water awareness, educate about the range of reuse options, and attract others who want to become a part of water conservation. “We focus on the simple systems that are more affordable and more customizable to people, but we also give people a huge range of ways to conserve and reuse water,” she says. Although she admits grey water remains a solution few talk about or consider, she is hopeful. “Grey water is not typically a part of the conversation, though I think that it should be,” Allen says. “And I think it will be. It will just take time.”

Marrisa Poe is a contributing writer and business officer for Rooted. Prior to obtaining her master’s degree in the Magazine, Newspaper and Online Journalism program at the S.I. Newhouse School of Public Communications at Syracuse University, she received a bachelor’s degree in English literature with a minor in business. While at Syracuse University she was a graphic designer for Perception and Medley magazines. Driven by her love for words and design, she seeks to create perfect story experiences for audiences to enjoy.