Twelve years ago, Amy Antonucci, a 48-year-old certified permaculture designer and homesteader, traveled with her partner about 30 minutes from their home in Dover, N.H. to collect bees. The pair packed the bees into a van but failed to notice a loose latch on the boxes. As they started back home, the bees slowly began to escape their hives and fill the van’s small space. Antonucci continued to drive as about 50,000 bees poured out of the boxes, masking the sunlight in the car and closing in on the pair. The two beekeepers came prepared for unexpected challenges and wore their bee suits. But they forgot to fill the van up with gas before leaving that morning, and the fuel gauge began to near empty. Antonucci’s partner suggested they open the windows and let the bees go. But Antonucci refused to let $200 fly out the windows. So they stopped at the next gas station, jumped out in their bee suits, and filled up the van. Onlookers, who seemed perplexed by the pair’s hazmat-like suits, asked Antonucci if they knew something they didn’t. Antonucci replied: “As long as you’re not with us, you’re fine.”

The two made it home safely with their bees, and despite the initial drama, they don’t regret their investment. Antonucci and her partner view the bees as a great addition to their permaculture lifestyle. The bees yield or provide many functions — namely honey, wax, and pollination. “The reason I got into all of this is I believe in people bringing these critical skills back into the community and being more local and being connected to the people around us instead of depending on corporations,” Antonucci says.

Around the same time Antonucci decided to invest in bees, beekeepers reported unusual high losses in hives. In the winter of 2006 to 2007, colonies were hit with cases of Colony Collapse Disorder (CCD). CCD occurs when there is a sudden loss of worker bees, but the queen and young remain, along with more than enough honey and pollen for the hive. The hive, however, cannot survive without worker bees and will ultimately perish.

The loss of honey bees due to CCD, parasites, pesticides, and lack of flowers prompted a public outcry. Documentaries such as the 2009 Vanishing of the Bees narrated by actress Ellen Page, films such as the 2008 The Happening by M. Night Shyamalan, which features Mark Wahlberg as a science teacher concerned about the sudden disappearance of bees, and reports of the potential extinction of bees sparked a growth in bee awareness and interest in beekeeping. In 2017, Cheerios joined the voices of bee concern and removed Buzz, the iconic bee, from boxes of Honey Nut Cheerios to raise awareness. “Buzz is missing because there’s something serious going on with the world’s bees,” the company posted. “Bee populations everywhere have been declining at an alarming rate, and that includes honeybees like Buzz.”

The more publicity the declining number of bees received, the more aspiring beekeepers wanted to help. Molly Keck, an entomologist and extension program specialist at Texas A&M AgriLife Extension in College Station, Texas, teaches educational programs related to bees and beekeeping. Keck has noticed a continued increase in curiosity in beekeeping from her students. “It’s kind of been a trend, and because it’s coming back in trend, there are more places for people to get the equipment and other things,” Keck says. “Whereas before, everything was through a catalog, so it was a little bit more daunting. Now, it’s a lot more local and easily attainable.” Walmart, Williams-Sonoma, Etsy, and Amazon all sell beginning beekeeping materials.

The reason I got into all of this is I believe in people bringing these critical skills back into the community and being more local and being connected to the people around us instead of depending on corporations.

Antonucci, who has been keeping bees since 2005, echoes Keck’s experiences. She also educates people about bees and beekeeping and has seen a growth in interest and practice. She is the founder and director of Seacoast NH Permaculture, and in that role, she educates new beekeepers in New Hampshire. She says her monthly beekeeper club meetings continue to grow with new members. At her first meeting 15 years ago, before she bought her bees on that dramatic drive, the club consisted of 12 members. Now, at the most recent meeting in March, the gathering included around 75 attendees.

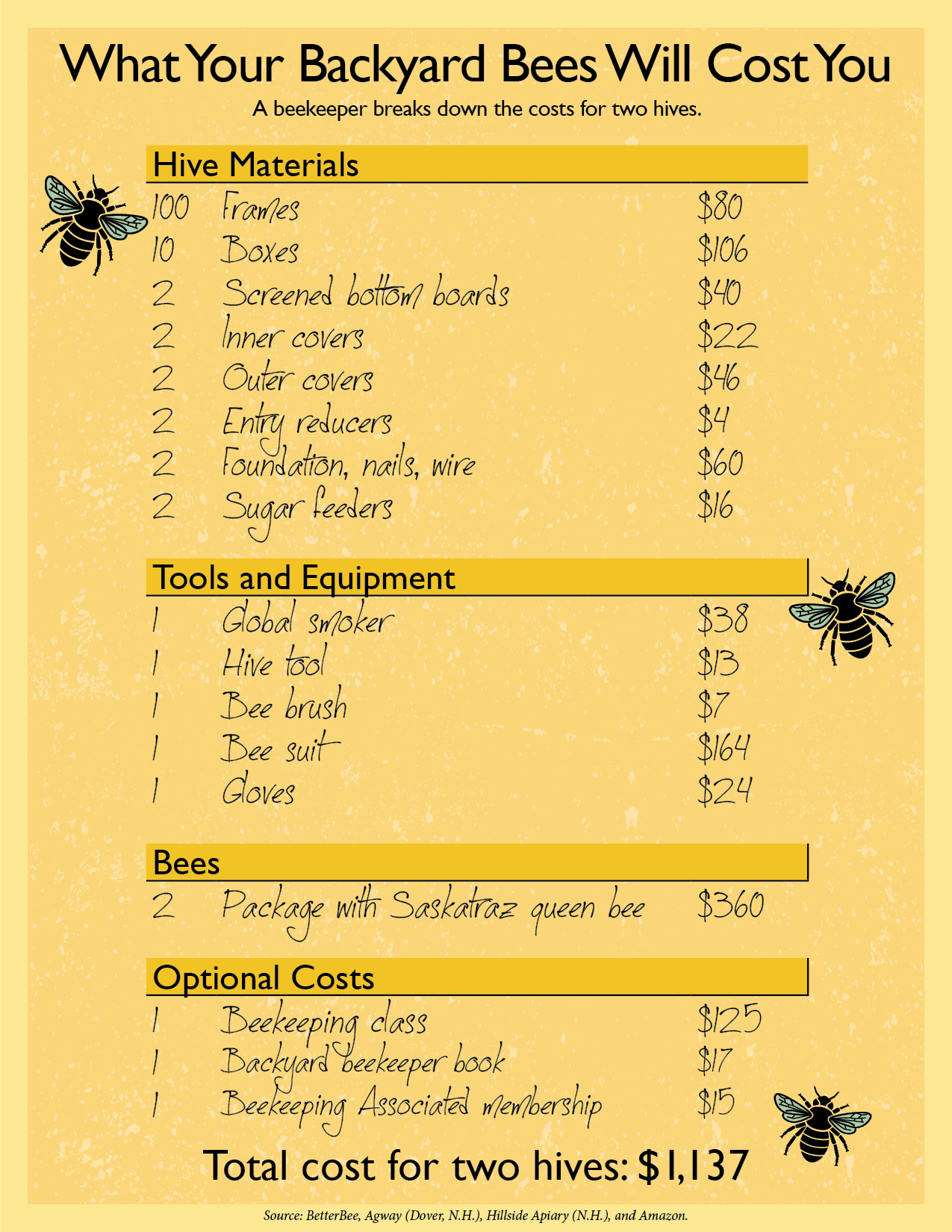

One of the newest members of the Seacoast Beekeepers Association is Ellen Brooks, a former student of Antonucci’s. Brooks never imagined herself as a beekeeper, but the environmental engineer’s passion for nature coupled with her curiosity led her to Antonucci’s beekeeping course after the 25-year-old saw a sign for the class posted at a local coffee shop. Like many before her, Brooks took notice of the declining bee population and resolved to become part of the solution to save the bees. The six sessions of two-hour-long classes at Seacoast Permaculture cost $125 and started with the basics of honeybees, a primer on the different breeds, and an overview of how hives function. The classes progressed to learning how to install bees in a hive, prepare hives for winter, and identify diseases or pests in the hive.

“The more I learned, the more fascinating it was,” Brooks says. When the classes ended, she purchased her first two colonies of bees, driving an hour out of the city to collect her bees and packing two colonies of 6,000 bees in her car. She says she drove home carefully, accompanied by a soft humming of buzzing bees. Once home, she transported the colonies into their hives, taking the queen bee out of her cage and into the hive so the remainder of the colony can catch her scent and follow. Then, she lightly tapped the boxes the bees came in and poured them into their hives. Brooks remembers other beekeepers telling her the first time she dumps a package of bees would be one of the most exciting parts of the process. “You have to do it yourself,” Brooks says. “It was one of those cool experiences.”

Most beekeepers describe their first day with their bees as memorable. That’s how Bill Kaufman, a beekeeper of more than 15 years and owner of Kaufman Family Farm in Bridgeport, N.Y., describes his first day. He specializes in hive management, colony removal, and bee sales. He’s also a consultant for beginning and veteran beekeepers. The first time Kaufman, a 40-year-old father of four, purchased his bees, he was terrified. “I was scared to death,” Kaufman says. Thousands of bees buzzed around him boosting his adrenaline as he opened the package of bees and dumped them in their hives. Three days after, Kaufman still felt the sensation of buzzing bees crawling on him. Fortunately, that fear transitioned into a passion, and for the last two years, Kaufman has transitioned his passion to a full-time business.

Although she’s still in her first year as a beekeeper, Brooks says she has learned about patience and the importance of maintaining her bees. “It’s one of those things where it’s challenging to think about all the time, especially with these two hives,” she says. “Someone local who beekeeps was telling me, ‘You know they’re like kids. No two kids are going to act the same.’ And it’s the same with my two hives. One of them is acting completely different than the other.”

The more I learned, the more fascinating it was.

Brooks installed her two hives at the same time, but after noticing one hive seemed busier and produced more honey, she consulted her bee association and beekeeping Facebook groups to share her concerns and look for advice. Ultimately, Brooks concluded that the difference in hives came down to the queens. One queen bee was stronger than the other and thus produced eggs more quickly, which resulted in more bees and honey.

To combat the lack of egg production in the weaker hive, she took one frame from the stronger hive and placed it with the weaker one to see if it sparked any change. The weaker queen came out of hiding and started laying eggs again, but Brooks is still keeping a close eye on her. If her low production continues, the hive will most likely not survive the winter and die. For comparison, the stronger hive has already grown large enough to fill two boxes, but the weaker hive is only inhabiting one box and only producing a quarter of the honey and bees of the stronger hive. In the next week or so, Brooks will decide if she needs to requeen her weak hive and has already been in contact with a queen breeder in Maine. “If I’m going to do something, I need to do it soon because if it keeps going at this rate they probably won’t be strong enough to make it through the winter,” Brooks says.

Brooks’s goal for the end of her first year of beekeeping is simple: keep the bees alive in the winter. “Right now, my concern is, I’m trying to get them to a point to prepare them for their first winter,” Brooks says. After that, she looks forward to the honey that her two hives will produce next season.

Additional reporting on this story by Randy Plavajka.